When Mother Seton started St. Joseph’s School (later Academy) in 1810, she made it a point to include the very practical skill of needlework into her curriculum for the young girls who attended the School. Many of these needleworks survive in the archival collections of the Daughters from across the span of the 19th century.

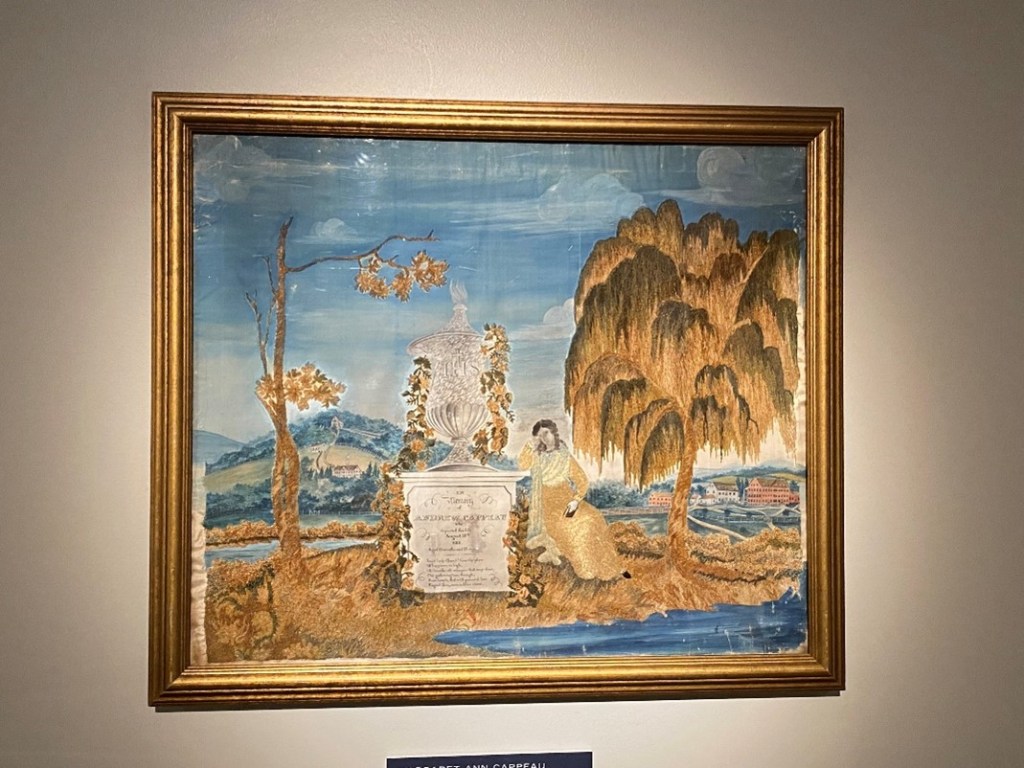

The incorporation of needlework into the curriculum served to teach skills in the arts, religious instruction, the beginnings of basic literacy, and practical skills for 19th century feminine life that prepared the girls to be proper 19th century women. Many of the needleworks in the collection combine multiple mediums, with a background painted in watercolor and the silk embroidered on top of it, as with this piece shown below by Margaret Ann Cappeau (began her studies in 1826).

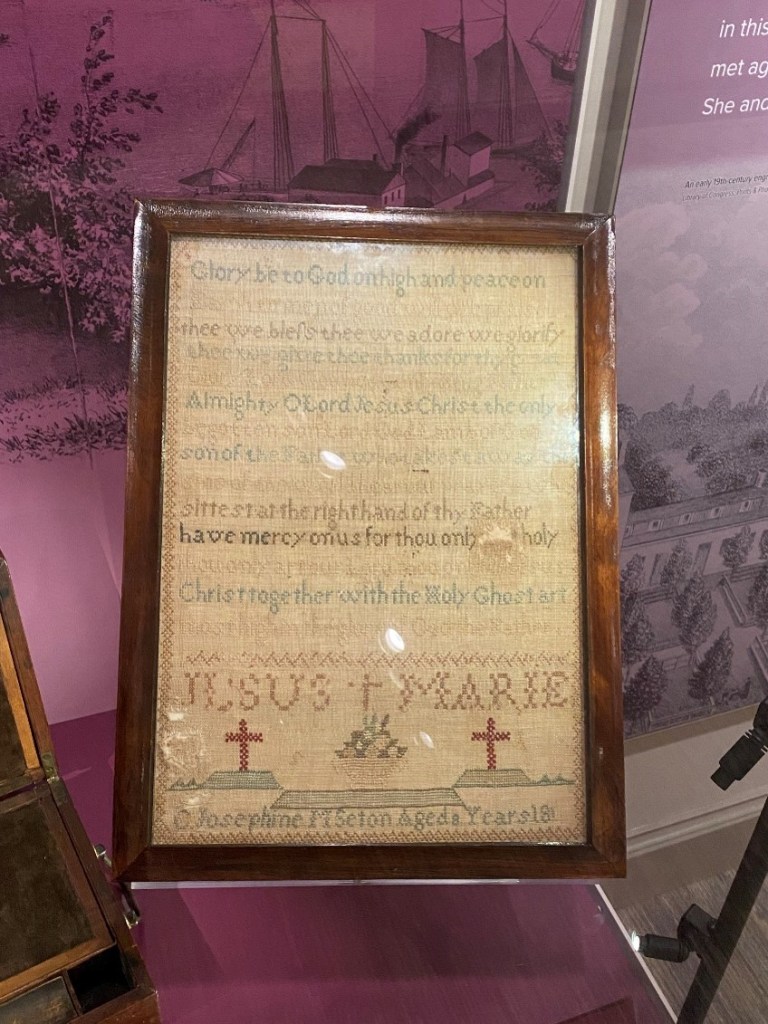

For literacy and instruction in religion, many students started with basic letters and numbers. When they had mastered these tasks, they advanced on to stitching out verses of scripture. Mother Seton even helped her daughter Catherine with her needlework and early learning on this front.

In addition to being records of the curriculum of the Academy, the needlepoints also serve as some of the earliest records of the evolution of the School’s campus. A common subject of the needleworks is a depiction of the school itself, and, in the era before photography was invented or common, the images created by the students provide the earliest visual records of how the campus grew and evolved.

Other needleworks contain stories of their own. Belle Barranger began creating the largest needlepoint in the collection on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg, when the School was evacuated and temporarily closed as both the Union and Confederate armies marched through town. As she tried to finish St. Patrick and his destruction of the serpents, she did not have time to finish the serpent itself! As the piece passed from one generation of her family to the next, so too did the story and what it represented, until her descendants, still knowledgeable of the Daughters, donated it back to them for posterity after their mother’s death.

These samplers were common in Maryland and have a distinctive style. Today, they are exceedingly rare and valuable, with the Daughters of Charity collection being one of the largest, with nearly 40 samplers dating from 1812 to 1940. Many of the samplers from the collection are currently on display in the Seton Shrine Museum through the end of 2024. They can be viewed both as beautiful pieces of artwork or as pieces of documenting the history of education in Emmitsburg.