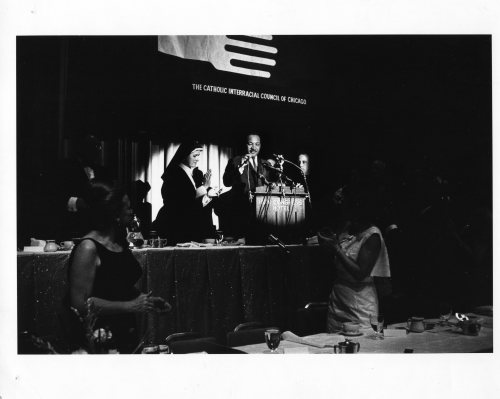

Five years ago, the Daughters of Charity Archives began to thoroughly investigate the relationship between the Sisters and the Black community. There were known stories certainly, such as Sister Mary William Sullivan and Martin Luther King for example, or the long relationship between the Sisters and the Briscoe family in Emmitsburg.

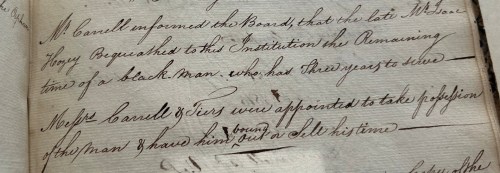

The collections also contained materials that showed a relationship between the Daughters of Charity and the institution of slavery prior to the Civil War, such as the Mary Dorsey document, which created a bond of an enslaved woman in exchange for tuition in 1856, or the Community’s acceptance of sixteen enslaved persons to work at Charity Hospital in New Orleans.

Over the last five years, we have tried to systematically examine the collections to document the relationship of the Daughters to slavery and the relationship with the Black community – the good and the bad.

We have tackled and examined the types of records that most easily come to mind for us and that can be moved through with relative ease – tangible items like diaries, Council records, and first-hand accounts from ministries below the Mason-Dixon line. We are facing one of our last biggest hurdles in the process, which is the systematic examination of the financial ledgers. This process is made more difficult by the relative lack of attention paid to these ledgers until now with regards to any topic. Many of the books had been simply labelled “Financial,” but we had not really learned how to use them.

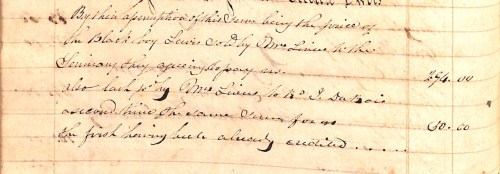

The process is also made difficult in communication. The early Community, founded by Mother Seton, was the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s. In 1850, they merged with the French Community to become Daughters of Charity. This is a distinction in the nitty-gritty terminology of the Catholic Church, but which requires explanation to all but the most-versed in the history of the Sisters. Through these processes, we have discovered significant and valuable information, some heartening and some disheartening. Working with our colleagues at Mount St. Mary’s University Archive, we received access to some of their early records, which verified an agreement to accept labor from an enslaved man named Lewis of the Livers family.

We discovered the acceptance and sale of an indentured servant in Philadelphia St. Joseph’s Home, the first ministry of the Daughters in the United States outside of Maryland, although the Sisters themselves did not have input on this decision.

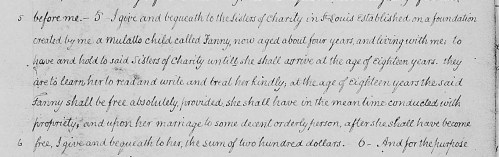

We discovered that the Sisters did have input on some decisions of the enslaved at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, that the enslaved were tasked with removal of bodies during the epidemics of the late 1830s, and that all were sold and replaced with hired white labor. Working with a researcher in Louisiana, fluent in French, we discovered the names of each and every person through the surviving sacramental records.

We discovered that the Sisters made a political statement in the opposite direction in 1830, when the Council decided “to help Simon in getting his wife free by some arrangement with her owner, & Simon.” We are still searching for some further clue or mention of Simon or his wife.

Thanks to a researcher-intern, we discovered further evidence of just how reliant the Sisters were upon Catholic benefactors who were also enslavers in slaveholding states like Missouri in the early days.

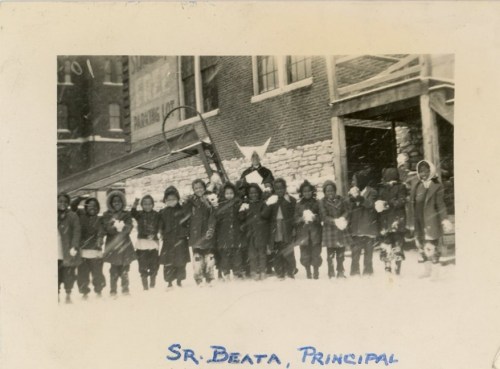

We also rediscovered entire collections pointing to elements of the Community’s history and our local and national histories. The St. Malachy School in St. Louis was a Black Catholic school before integration, which documents the experience of St. Louis’s Mill Creek neighborhood. Other historically Black Catholic parishes have collections too, including the Cathedral School in Natchez, Miss.; St. Stephen’s School in New Orleans; and St. Theresa’s Parish in Gulfport, Miss. The Daughters were also involved in teaching both during eras of segregation and eras of desegregation in Emmitsburg; Norfolk, VA; and Greensboro, NC.

Most importantly, we discovered the trove of local history that the financial ledgers provide in regards to the surroundings of Emmitsburg in Northern Frederick County, Maryland. At the far fringes of the county, much of its local history, white and Black, gets overlooked in favor of Frederick City. The financial ledgers reveal the finances of a small rural town, the comings and goings of people and merchants, and the complex interlocking web both free and enslaved families in the area.

Take, for example, Ann Coates/Coales, whom we discovered in the “Talks of the Ancient Sisters” speaking for herself:

Ann Coales, colored – “I used to work down here at the washhouse in Mother Rose’s time, bought my own freedom – ten dollars a month and allowed me nothing for my clothes.”

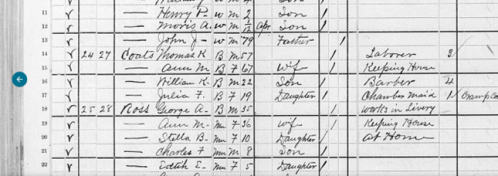

Ann makes further appearances receiving pay from the Community in Financial ledger 58 in September 1823, alongside a Henry Coates, Betsy Coats, and Mary Ann Coats. In 1845, Ledger 70, we suddenly see a new name: Kelly Koats (Thomas), that forced us to draw some connections and gave us new pathways for research.

We began to search for Thomas Kelly Koates and all associated spellings. In the Baltimore Archdiocesan marriage records, we found a match, and found his marriage to a member of the Butler family. Sure enough, we see them as husband and wife in the federal census records.

With this information, we can now connect the two families and find Ann even further back in the records under the name Ann Butler, who appears throughout the records as well! Using these names, we can help compute the family trees of the local African American families, their lives, professions, and to a certain extent, their moves in and out of the area!

This work is certainly slow-going at times – we must also complete all our other work as well after all – but we are updating our research and subject guides on Slavery and African American History when we make it through a new ledger. Their current iterations can be found here and here.

Check back from time to time and join us on this journey! The Daughters of Charity Archives is excited to be a partner in the processes of research, accountability, and reconciliation.

We must also thank our interns, volunteers, hired researchers, and colleagues at the Seton Shrine for their hard work and dedication in this process. The value of your contributions cannot be overstated.

![Typewritten text reading: "June 28, 1966[.] Dear Mrs. Stevens and Miss Massa, I am addressing this letter to both of you so that together you will learn all about the last days of your dear Sister and our beloved companion. Sisters is a great loss to all of us as we all loved her and admired her for her kindness and her holiness. Sister was on active duty all day Saturday, June 25. She served our chaplain's breakfast and did all the other little things that she did all day, the last of which was to go around the home and bless the little children with Holy Water. This gave Sister the opportunity to meet all the personnel and to keep in touch with the children she loved so much."](https://docarchivesblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/picture3.png?w=500)

![Portion of a letter from Mrs. C. Lagario reading: "These are the names of Sisters relatives. Mr. Frank Montegane[,] Mr. & Mrs. I. Montegane[,] Mr. & Mrs. H. Bawers[,] Mr. & Mrs. M. Schenone[,] Mr. & Mrs. . Lamerdin[,] Mr & Mrs. H. Gaerndt[,] Mr. & Mrs. J. Labario[,] Mrs. Caroline Labario Our prayer are with you. Mrs. C. Lagario"](https://docarchivesblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/picture4.png?w=500)