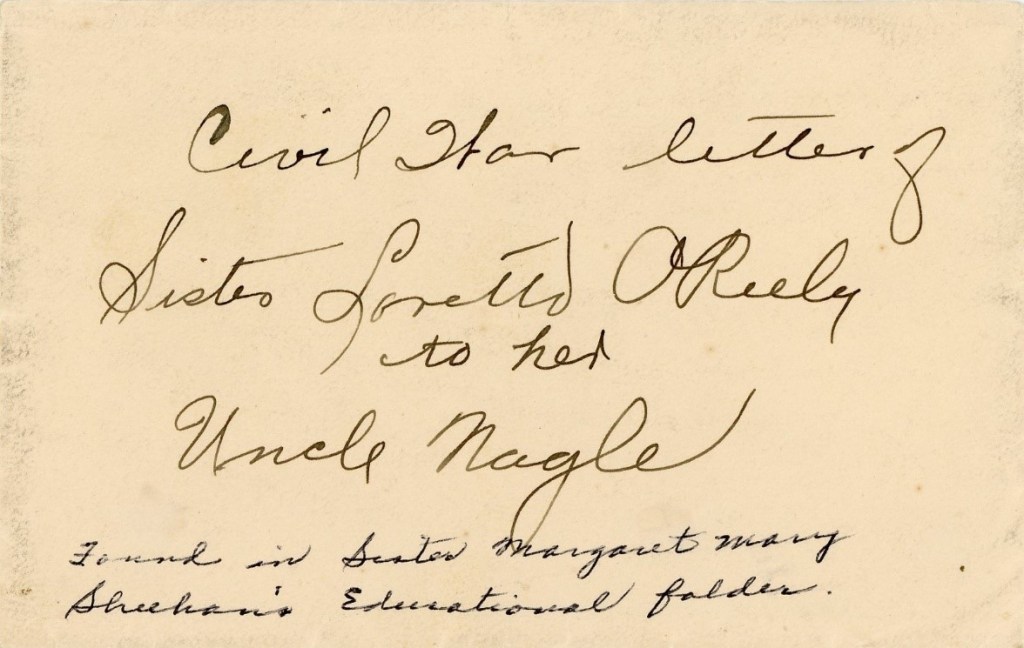

In April 2022, the Archivist for another community of Sisters reached out to a number of other Archivists from other religious communities, asking about a Sister Loretto O’Reilly who served in the Civil War. The Daughters were able to claim her, so we responded.

The Archivist went on to say that she had a set of letters written from Sister Loretto to her uncle in their collection and would like to repatriate the letters back to their home collection. We happily agreed to accept the letters when she next travelled through the area next.

Two and a half years later, the transfer finally happened.

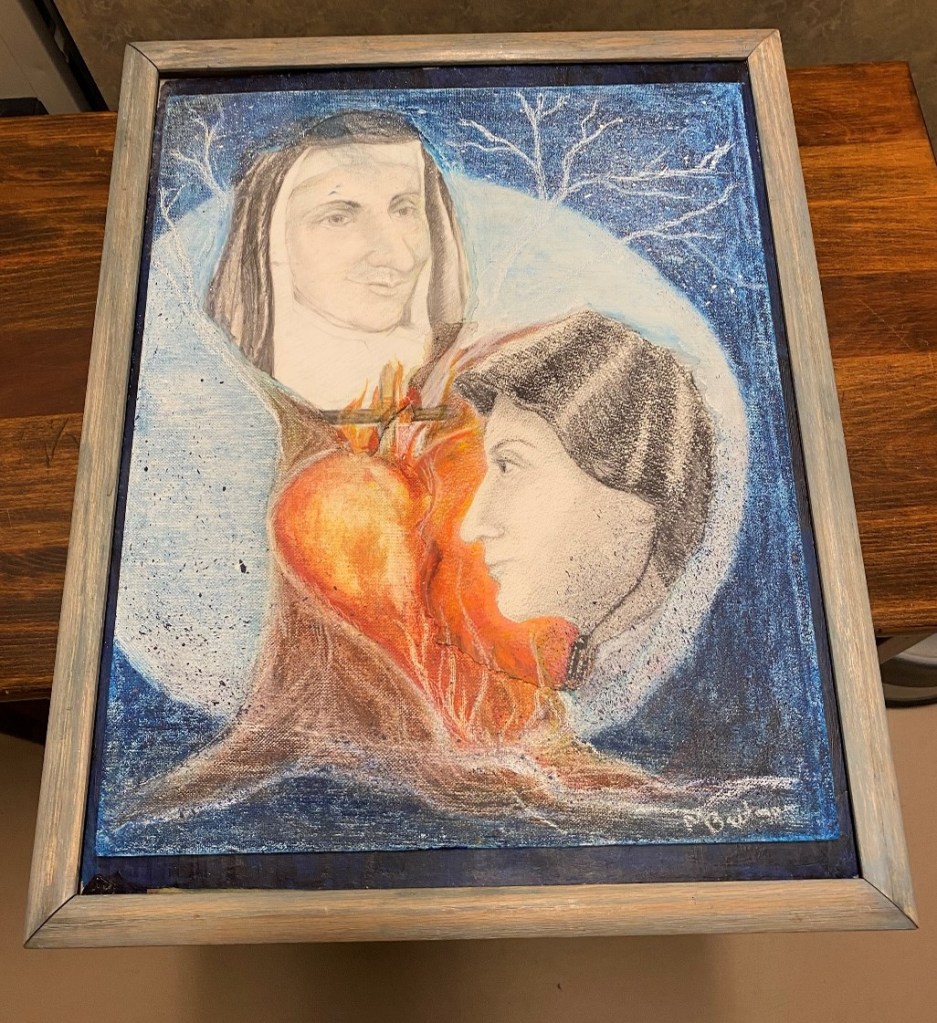

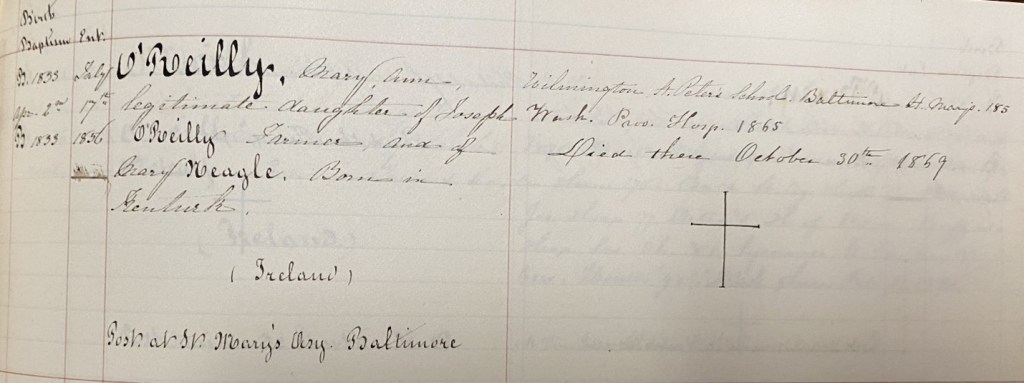

Prior to the transfer, the Archives had some information about Sister Loretto. We knew she was born Mary Ann O’Reilly. She immigrated from Ireland in 1853 and that her parents were farmers. We know she joined the Community in 1855 and served in a few schools and infant homes prior to 1861. When the Civil War began, she served as a nurse in Cliffburne and Lincoln Hospitals in Washington, D.C., where she acquired the moniker “Guardian Angel of the Ambulance.” She became the second administrator of Providence Hospital in Washington in 1865, a position that stemmed from her work at the D.C. hospitals, where she was vital in establishing the Hospital in the post-war years. She died at age 37 in 1869 of an early-onset heart condition.

There are two known photos of Sister Loretto.

As best as we can conclude, the letters were used by a Sister of St. Joseph as a teaching tool, coming from their Wichita chapter. They are marked as “Found in Sister Margaret Mary Sheehan’s Educational folder.” In total, there are six complete letters from Sister Loretto to her uncle, one incomplete letter between the same, and one additional incomplete letter from her uncle to a woman named Mary.

Prior to these letters, we did not believe any of her own personal accounts still existed. The information about her time in the War came from the Civil War Annals, and, while these are massively valuable resources, they suffer from two drawbacks. First, they were written as recollections in 1866, not as accounts written in the moment. And second, they often discussed locations in general in a few pages, not the works of individuals. At Cliffburne Hospital, accounts describe a night of 64 men arriving, with “only eight [who] had all their limbs.” In spite of the challenges, doctors and nurses tried very hard to care for their patients’ physical and spiritual conditions, among the challenges being an outbreak of smallpox that required quarantining of some soldiers. Alongside the Sisters’ works, there was also evidence of collaboration with the government, with accounts of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln herself bringing donations of supplies to soldiers who had been in residence for an extended period of time!

The letters go into much more extensive detail about life and work at the Hospitals. On August 10, 1862, Sister notes that there are 15 Sisters and 13 doctors working at Cliffburne, with attendants to do “the cleaning, etc.” She also described the political state of the Hospital: “When we first came here there were nearly two hundred Confederate prisioners [sic] confined here. Many of them badly wounded but as they got better they were taken to the old Capitol and confined there until they were exchanged.” They received care, and she notes with some surprise that the “Confederates got more visitors than the Union soldiers.”

Her November 28th, 1862 letter attests to a few conversions among the soldiers, but shows her anguish at what she considers many soldier’s “indifference” to their spiritual lives. She goes into detail about the Cliffburne itself, describing it as a converted barracks for the cavalry, so many of the wards are actually horse stables: “It is a very nice place for a summer Hospital, but it is inconvient [sic] for winter.” She says that the Hospital fit 2,000, that their patient population had topped off at about 1,400, but was down to 600 by November. “I think it is about one mile square or neally [sic] so. There are seven long wooden wards or Barracks each containing seventy-five beds and forty-two tents each contanes [sic] eighteen beds, scattered about a large space besides there are a number of other buildings such as store houses, kitchens mess rooms etc.”

By April 26, 1863, Sister Loretto had relocated to Lincoln, the largest field hospital in Washington: “It is composed of twenty large wards or Barracks build in the form of a V, ten each side and one large one in the center which is used as head quarters the Doctors rooms, offices, dispensary, etc. Each Ward holds from sixty to seventy beds, they are high and well ventilated.” Her personal thoughts: “I like the Wards and the hospital generally but the situation is miserable. It is a swampy hollow place and a perfect mud hole.” They had begun receiving patients shortly before Christmas 1862 from the Battle of Fredericksburg. The Battle was one of the most lopsided victories for the Confederacy of the War, and Sister calls it “not a Battle but a slaughter [emphasis hers].” By May 1, 1863, many of the soldiers from this battle are still at the Hospital, and Sister notes that “I saw them realize what War is or at least see the fruits of it.”

By July 3, 1863, there had been even more major battles: “Since my last letter to you we received a number of sick and wounded. The wounded were all from a cavalry fight a short distance from here [likely the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863]. They were brought to the hospital the day after the battle. They are not making preparations for a great many from the battles now going on [possibly Gettysburg]. Nearly all the prisoners have been exchanged. We have only ten or twelve here now. Only a few of them died.” She expresses the hope for the end of the War: “I am sure you have heard of the great excitement in this quarter for weeks past. I wish every day more and more that this war ended. It is dreadful to think of the number of poor souls plunged daily into eternity and the misery brought into thousands of homes. Tho so long accustomed to witness their sufferings I can not get used to it.” Finally, her time with the common soldiers revealed to her the longstanding and common divide across time, generations, and Wars between the common enlistees and draftees and their commanding officers, particularly after the long string of losses the United States suffered early in the early years of the War: “The poor men too, are so discouraged at (as they say themselves) getting whipped all the time and blame their officers very much with very few exceptions they all seem tired and disgusted with the war.”

In the last letter of hers in the collection, from November 1, 1864, an incomplete letter, she comments on the soldiers’ and their political talk in the wards, as they expect more wounded from the battlefields in Virginia, and her note that many of the soldiers she encounters tend to be supporting the election of the former general Scott McClellen over President Lincoln in the upcoming election.

As fascinating as her accounts of the Hospital and wartime life are, the letters help flesh out her life in far more detail than we have ever had before. Based on these, we are able to draw conclusions about her early life and her family life far more than we ever have before. She makes reference to writing to her parents, entirely separately from her uncle and apparently back in Ireland: “I was truly sorry to hear such accounts of our poor Ireland and it makes me still more anxious to hear from my parents.” When Sister Loretto immigrated to the United States in 1853, Ireland was still in the worst days of the Great Famine, and she brings up two names of siblings as well, Mage and Lizzy. By July 3, 1863, they have relocated to Dublin, despite listing her father’s occupation on her community entry papers as “Farmer.” Seemingly, the city offered better opportunities than continuing to farm.

The final letter in the collection was written by her uncle in 1870, a year after Sister Loretto’s death, postmarked from Atchison, Kansas. Regarding her early life, he writes that “Since she left Saint Louis we kept up a regular correspondence. Her letters were always interesting to me and I miss her on that account as well as for their feelings. Though her education was not expensive her letters show that she made good use of the opportunities that she got to learn.” It seems likely that her uncle was her sponsor when she emigrated, and she possibly lived with him, considering the separation of her uncle and the rest of her family across the sea. She also received some level of schooling, possibly from one of the many Daughters of Charity institutions in St. Louis at the time.

It is even more impressive what he wrote about the final stages of Sister Loretto’s life, events which otherwise have not made it into the historical record and shows just how much the nursing prowess of the Daughters was respected in Washington. “A Member of Congress invited her to command their Carriages when she wished to take recreation, but she never used that privilege. The President even paid her the honour of a visit. Thadeus Stephens” – the famous Congressman and advocate of a Radical Reconstruction following the Civil War – “a member of Congress who successfully contended for a grant of money to assist in building Providence Hospital was at the point of death. Mary Ann [Sister Loretto] with several Sisters visited their dying friend and with the consent of those present she Baptized the dying Statesman.

These letters are not just a massively valuable addition to the Daughters’ Civil War collection, they illustrate a remarkable life that, while far shorter than it should have been, made an impact on hundreds or even thousands. It is a tribute to the nurses, the combat doctors, the Irish diaspora, and, certainly, the Daughters of Charity.

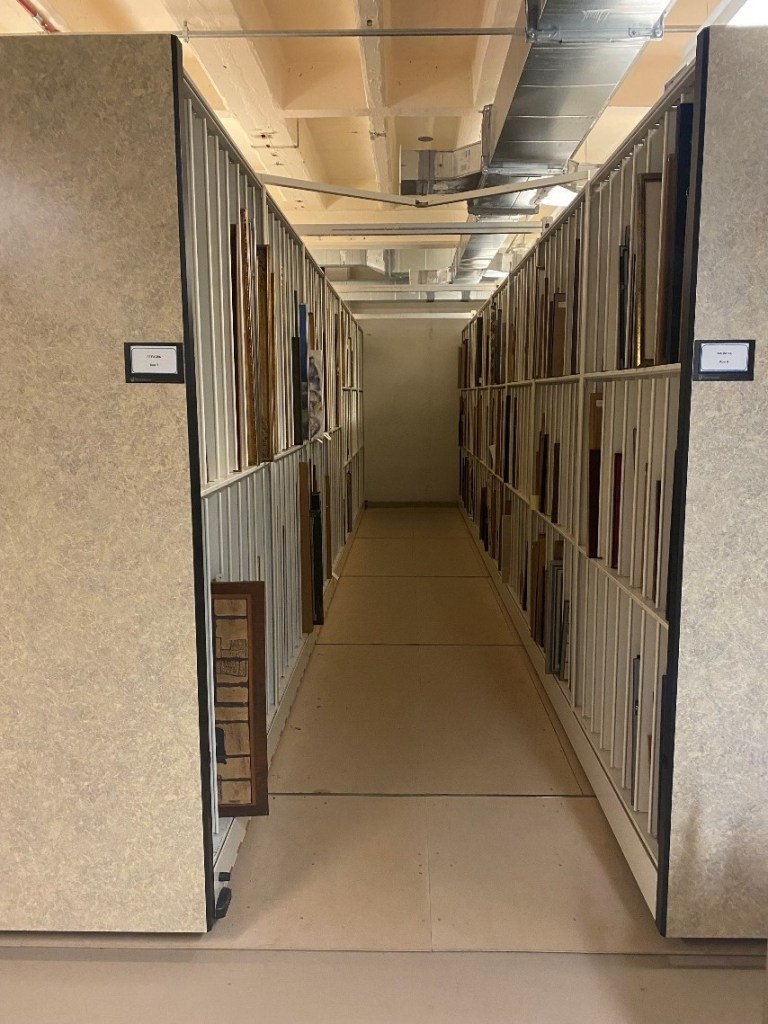

The letters are available for researchers alongside the rest of the Civil War collection.