Typically, in these posts, we try to focus on materials held here at the local Provincial Archives. For this post, however, we would like to focus on a piece of global news of the Daughters and the archival world.

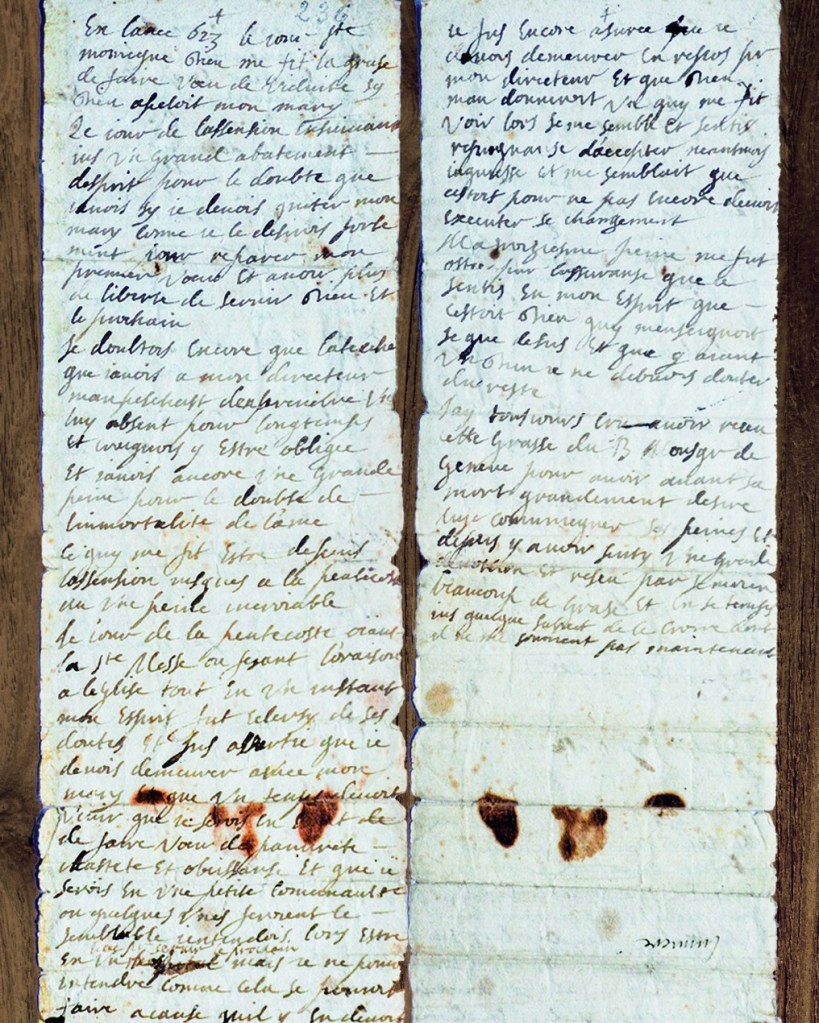

One of the foundational documents of the history and spirituality of the Daughters of Charity is the Lumière of Saint Louise de Marillac, the co-founder of the community alongside Saint Vincent de Paul. In 1623, on the Feast of Pentecost, Louise found herself in a deep melancholy, with her husband seriously ill, an uncertain future for herself, and a crisis of faith at hand. In a moment of prayer, she had a vision of the pathway of her life. She saw herself when she “would be in a position to make vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and that I would be in a small community where others would do the same.” She added, “I was also assured that I should remain at peace concerning my director; that God would give me one whom He seemed to show me.” She felt assurance that “it was God who was teaching me these things…I should not doubt the rest.”

It took a decade for the work of her vision to come to pass. She did find a spiritual director in Saint Vincent, and, in 1633, they together founded the “Little Company” of the Daughters of Charity. Saint Louise carried the folded message that she wrote to herself on Pentecost until her death.

The 400th Anniversary of this Pentecost has just passed. The folded note of Saint Louise had survived for centuries in the Archive of the Vincentian Fathers, Saint Vincent’s priestly community. As a magnanimous gesture and a symbol of the fraternal ties between the Vincentians and the Daughters of Charity, the Vincentians repatriated the Lumière back to the Daughters of Charity. It will live and be preserved in their Mother House at the Rue du Bac in Paris as one of the great historical and spiritual treasures of the Community’s charism!

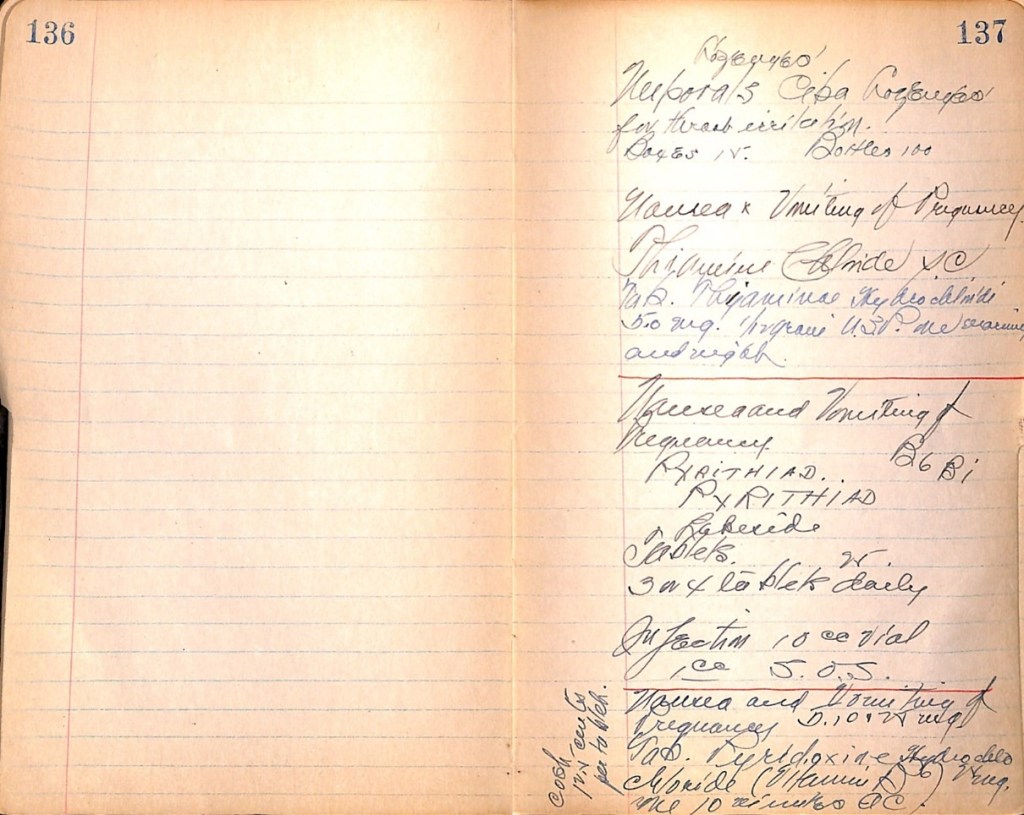

Although the Provincial Archives does not hold any primary sources of Saint Louise, we can provide a wide array of resources on Louise’s spirituality and the way it is interpreted and lived today through the Community that she founded. These include scholarship related to Louise and many works named after her, including St. Louise de Marillac School in Arabi, Louisiana; St. Louise de Marillac School in St. Louis; St. Louise de Marillac Hospital in Buffalo, New York; and the Association Louise de Marillac lay organization.