Research on the Lee family has been greatly assisted by the work of the “Recovering Identity” project of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. The Daughters of Charity Provincial Archives has assisted the project with resources where we were able, and we are grateful to them for the next steps they have taken and their extensive consultation of other sources. Their full reports and summaries and be found here.

Beginning in the late 1870s and going through the 1890s, the “Talks with Ancient Sisters” sought to gather the stories of some of the oldest Sisters and community members, particularly those who had been around in the time of Mother Seton. Speaking in 1884, Sister Helena Elder, a member of the Elder family, a longstanding, extensive landholding family of Emmitsburg, briefly mentioned a family named Lee: “I don’t know whether his name was Charles or not. A colored man and his wife. They lived up there in Brawner’s place,” Sister Helena said. Her interviewer added “I expect that’s the Lee [who] Bishop Bruté speaks of in one of his notes after Mother’s death when he says, ‘here looking across the fields from Charles Lee’s about one mile to the little wood.’”

Like several of the African American families of early Emmitsburg, a brief mention like this can begin to scratch the surface of life amongst the free and enslaved communities of Emmitsburg in a history that has only begun to receive attention within the last few years from local historians.

Father Bruté does in fact first mention Charles shortly after Mother Seton’s death in 1821:

I again shed tears near Charles Lee’s looking from the hill across the meadows one mile towards that little wood to day [sic], 19th May, 1821

The property of the Lees, overlooking the Valley where the Sisters established themselves, had been owned by Charles since 1813 on a property appropriately called “Pleasant View.” Charles is called in the Bill of Sale document “Charles Lee Blackman (formerly the property of John M. Bayard).” Indeed, Charles had purchased his own freedom in 1804 for £100.

Charles is remembered in the late 1880s by another local African American man, Augustine Briscoe. The Lee property had apparently remained somewhat famous, as he said “There, Sister, there is where Charles used to live. They were old settlers about here. Charles Lee was grandfather to Martin Lee; he was free but his wife wasn’t.” By 1810, Charles and his family were all living together, despite their mixed-freedom status, and, from 1807 to 1814, Charles purchased the freedom of his wife Hannah and children Isaac, Peggy, and Adeline from Elizabeth Brawner, another member of the Elder family. Their later children would be born free and never bear the struggle or indignity of slavery.

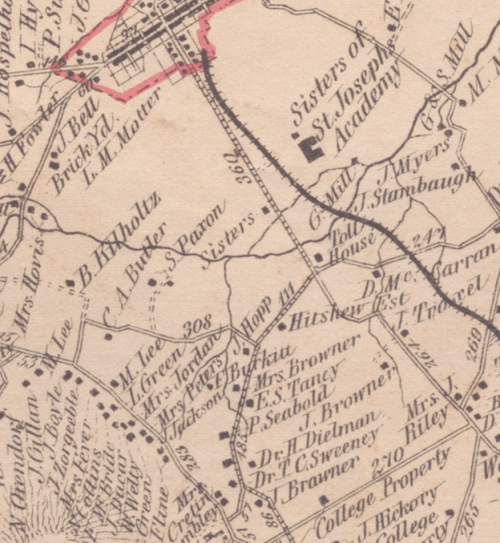

It points to the complicated interwoven strands of freedom and slavery that the Lee and Brawner properties are described as being so close to each other. Maps from the collection show their properties less than a block away from each other, and finance books show payments for activities to both families intermixed together.

References to the family in the Daughters’ archive pick up with Isaac, the first family member whose freedom Charles Lee purchased. Isaac Lee receives his own page in one of the surviving financial ledgers, indicating a long-standing set of payments and transactions between the two. From 1838-1839, the ledgers indicate that he was “employed by the month at $10 per month.” Notes that indicate the nature of the work include that portions of his payment come from “the Quarry Acct.” Further details emerge when one delves deeper into the transaction books to find that in addition to farm work, it includes “quarrying stones for a church.” Indeed, this lines up with the construction of the chapel of the new Central House of the Province, which today is the chapel of the FEMA National Fire Academy!

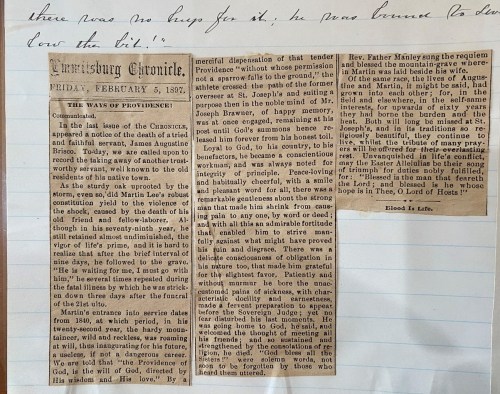

Martin Lee was not a direct descendent of Charles Lee, but married into the Lee family and chose to take his wife’s last name. The Provincial Annals contain a lengthy obituary of him after his death on January 24, 1897. He was described as a “faithful attache” of St. Joseph’s farm who had been devastated by the death of his wife Emily in later years. It is also stated that the death of his friend Augustine Briscoe, another member of another old African American family of Emmitsburg, had been a particular shock to him.

Martin had also put his earnings into purchasing real estate. He owned several small properties on the Mountain. After his death, he offered the Daughters the first chance to buy the property from his family, although the community declined to do so.

The research process is ongoing for details about the Lee family. In the near future, it is our goal to better understand and describe the many financial ledgers and cash books to make them easier to use, and hopefully to shed more light on the historic African American families of the Emmitsburg area!