This is a guest blog post by Leah Kanik, a Junior at Mount St. Mary’s University, class of 2027. She has been an intern with the Daughters of Charity Provincial Archives for Fall 2025 semester.

Sacred art has been a staple in the spirituality of the Catholic Church for centuries for its ability to raise the mind to contemplate the things of God. Humanity needs corporeal reminders of the supernatural to direct the mind and soul to higher truths, and art is a way in which this interiority can be reflected by the exterior. For those who use art to manifest the interior life, it is as if the longings of their soul were so strong that they must spill onto paper. Such could be said of Father Simon Gabriel Bruté, that “Angel of the Mountain” and first bishop of Vincennes whose influence transformed the places he ministered to. His drawings reveal the childlike simplicity of a priest who balanced peace of soul amidst the immense responsibilities of shepherding his people.

All of his extant drawings in the Daughters of Charity Archives predate his appointment as bishop of Vincennes in 1835 and instead cover his time at Saint Mary’s College in Baltimore and Mount Saint Mary’s University in Emmitsburg. After arriving in Baltimore from France in 1810, Father Bruté taught at St. Mary’s Seminary for two years before being assigned to teach at the Mount. In 1815, he was made president of Saint Mary’s College, but returned to the Mount in 1818 to toil in keeping the school out of debt and administering to the spiritual needs of Emmitsburg and the Sisters of Charity, of which he was chaplain.

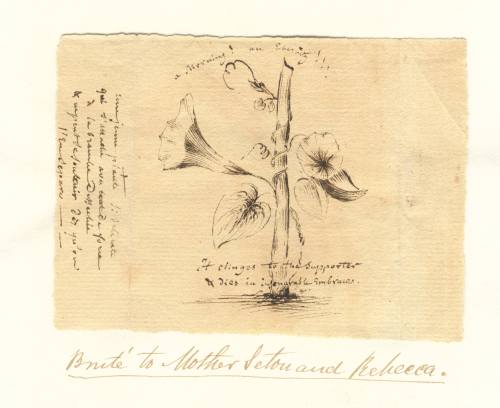

His priestly assignment at the Mount provided him with numerous opportunities to engage in his hobby of drawing. For example, his proximity to the Sisters of Charity during his time in Maryland enabled Bruté to become friend and spiritual director to Mother Seton, and thus many of the drawings are addressed to or depict Seton or her children. Other drawings outline the world of Emmitsburg as he knew it, relate his travels to France, or are simply a recreational sketch.

Whatever its context is, Father Bruté’s drawings predominantly include a reference to the divine which is reflective of his deep spirituality even in the most mundane things. This is seen in his more lighthearted sketches that show a kind of playfulness in using pen and paper to uplift the soul. He drew animals, landscapes, buildings, and religious symbols to supplement his letters and add beauty to the quotidian task of writing. Drawings about the reality of death or which are more historically significant also include an element of joy because of his faith in God and eternal life. No situation or created thing was exempt from participating in Father Bruté’s life of faith.

It is not the picture alone that manifests his interior life. Bruté uses Scripture or his own poems and prayers to pour out the aspirations of his soul. Even his historical drawings depicting the landscape of Emmitsburg or the sketch of his ship which took him to France have Scripture and prayers dispersed throughout them. They serve as reminders of his love and goal for Heaven. Indeed, a quarter of his drawings include the word “Eternity” as either central to the image or as a minor addition to a leisurely sketch. Even drawings in which the word is not explicitly written, the message of eternal life is implied by the belief in a home that transcends this world. Such was the nature of the drawings Father Bruté sent to Rebecca Seton for consolation in her illness, and this message of eternal life seemed to comfort even himself as he witnessed death within the Seton family.

Drawing was thus an outlet for Father Bruté during his labors in Maryland, but it was the responsibility of running Saint Mary’s and the Mount, helping the Sisters, and carrying out other priestly duties that were catalysts for his sketches. Perhaps the lack of drawings during his bishopric in Vincennes is due to his advanced age and increasing responsibilities, as well as having to care for a newly established frontier diocese that spanned the entire state of Indiana. Nonetheless, he utilized his ability to draw to link the temporal and spiritual worlds on paper, and so he encapsulates the purpose of sacred art in using the material to point to the divine. Whether one possesses the ability to draw like him or not, Father Bruté’s love of sacred art reminds us of the joy of the spiritual life and the necessity of preserving artistic beauty in the service of God.