Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the temple of the God of Jacob. He will teach us his ways, so that we may walk in his paths. The law will go out from Zion, the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He will judge between the nations and will settle disputes for many peoples. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore.

-Isaiah 2:3-4

We would like to take this opportunity to highlight a few Daughters of Charity of this Province who served their country prior to joining the Community.

To clarify, this post will NOT be about the Sister-Veterans of the Civil War, who served during their Community lives. Nor will it be about the Sister-Veterans of the Spanish-American War, World War I, or World War II who did the same. This post is merely about four Daughters of Charity who, during their lives before joining the Community, served something greater than themselves in a slightly different way during the Second World War.

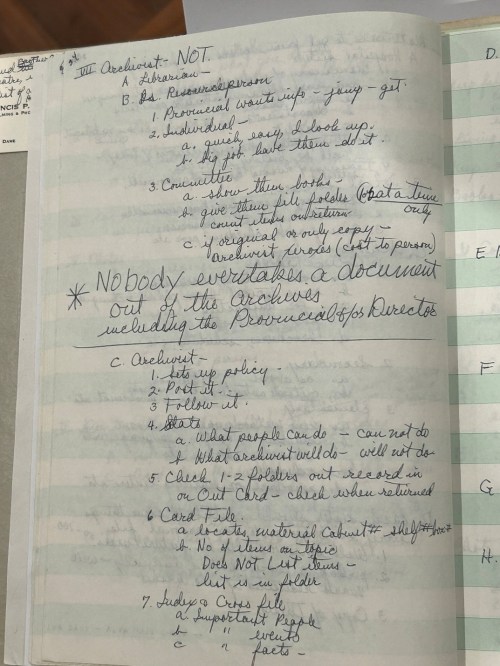

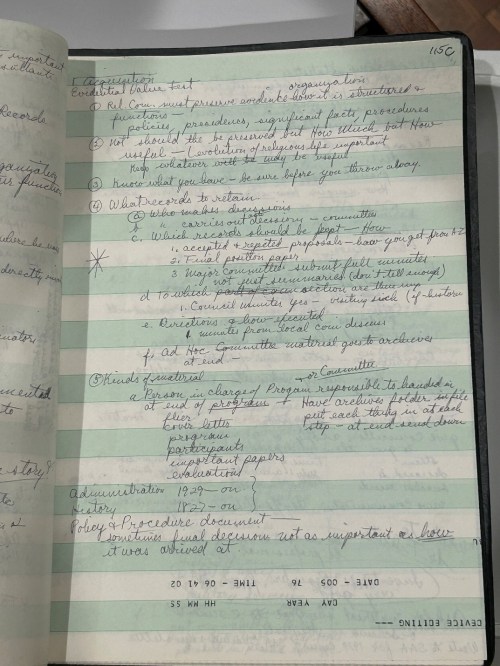

This post is also not meant to disparage or ignore the service of any Daughters of Charity whom we failed to include here. “Veteran status” is not a search terms that we filter for among the Daughters whose files are in the Archives. It is more something that we stumbled upon over time. It also may open the possibility of a part 2 in the future…

So, without further ado:

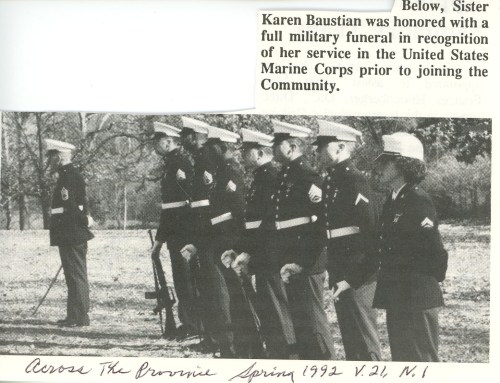

Sister Karen Baustian

Sister Karen started as an unenlisted electronics tech for the Army Air Corps, the future U.S. Air Force, following her brother into the service. She then enlisted in the U.S. Women’s Marine Corps in 1943, serving for 27 months as a Radio Tech. She began her service directing communications on the Paris Island Marine Corp base in South Carolina before volunteering for active service. This took her to Hawaii, where she repaired equipment for use in the Pacific Theater of the War.

After her honorable discharge in 1945, Sister Karen remained in the Marine Corp. Reserves until 1949. Looking to continue in her line of work after the War in Minneapolis, she was rejected from numerous jobs for being a woman. She instead utilized the GI Bill to go to school for broadcast journalism and for the next eight years worked in radio broadcasting in the rural parts of the state. As she traveled around the state in the 1950s, she began attending Bible study and growing in her own faith, when a priest directed her to the Daughters of Charity.

Sister Marguerite Eavey

Seeing that she had no brothers to represent her family in the War effort, Sister Marguerite volunteered at age 20 for the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (or the WAVES Program). Her service as a Pharmacist’s Mate, 1st Class, lasted from 1943 to 1945 and occurred at the Naval hospitals in Philadelphia and Norfolk, Virginia. She translated this service into attending the Worcester School of Business and becoming a secretary for the Department of the Interior after the War ended.

At age 30, she returned to her hometown of Martinsburg, West Virginia, where she went to school under the Daughters and applied to enter the Community.

Sister Regina Lindner

Another WAVES veteran, Sr. Regina Lindner actually began her Seminary as a Daughter of Charity, stopped to serve in 1941, and returned to the Community later. She also achieved the rank of Pharmacist’s Mate, 1st class, serving in Naval hospitals in California. Four more of her siblings remained with the Daughters of Charity, while Sister Regina returned home after the War to care for their ailing mother. In 1947, she returned to the Community to complete Seminary.

Sister Margaret Albert Scholl

Sr. Margaret Albert began her career in the U.S. Public Health Service, but very quickly enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard Medics in 1944. The Coast Guard at this time was patrolling the Atlantic and guarding the homefront in the event of a possible invasion of the East Coast. At the same time, based at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, she trained other paramedics for service in distant theaters of the War. Her service lasted from 1944 to 1951, and she joined the Daughters of Charity immediately thereafter.