The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was a watershed moment in American history. With major activities occurring and organizations active around our nation’s capital, site of the Daughters’ Providence Hospital, there was intense interest in the Movement. Although we do not know who created it, the Providence Hospital collection contains a scrapbook detailing this information.

The scrapbook is titled simply “Civil Rights, 1963-1964.” It contains newspapers from both Catholic and secular publishers documenting the events of the Civil Rights Movement in Washington and the surrounding Archdiocese. The very first page of the book contains articles about Archbishop Patrick O’Boyle’s outreach efforts to the Black community, an op-ed in favor of integration of the District’s hospitals, and, perhaps most notably, a schedule for the August 28, 1963 “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” These three topics recur consistently throughout the book.

These days’ newspapers, quite simply, capture one of the single most important events in American history.

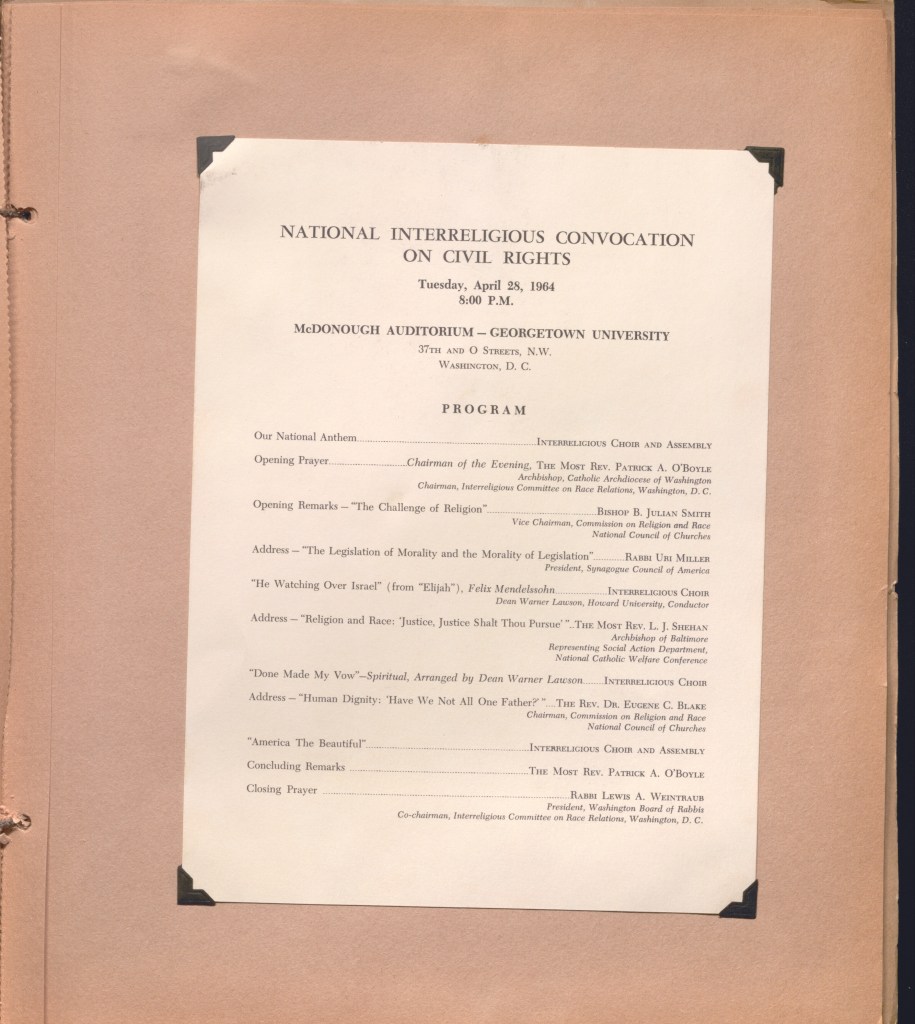

The future Cardinal Patrick O’Boyle was known as a strong religious and Catholic ally to the Civil Rights Movement, who made it a priority to desegregate the institutions under his jurisdiction when it was still deeply unpopular in much of Washington or southern Maryland. He provided the Invocation for the March on Washington as part of the interracial and interfaith program. During the debate over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, he chaired the Inter-Religious Convocation on Civil Rights at Georgetown University to lobby Congress to pass the act.

The scrapbook even contains the copy of the Congressional Record when the Act was passed.

We close this, of course, with the most famous words of that day, and an exhortation to take them to heart in the face of the Civil Rights’ struggles that remain in our way. Advocate and organize in the example of Archbishop O’Boyle or Dr. King.